AutoFixture Basics

Have your unit tests become a ball & chain?

Are small changes in your application breaking all of your unit tests?

Thinking about scrapping unit tests completely ?

In this blog series I’ll show some problems in the way unit tests are often written, and how you can take advantage of AutoFixture to help you get back to having unit tests that are a benefit instead of a burden. My goal is that by the end of the series you will a good understanding of AutoFixture and its benefits, and that you will feel confident enough to use it in your own projects.

So What is AutoFixture?

AutoFixture is a library created by Mark Seemann to help developers write code in a TDD style, but it’s just as relevant if you write your tests after the fact rather then TDD. The primary focus of AutoFixture is to create anonymous data, but over the course of this series you will see that AutoFixture offers much more than this.

An Example to Start From

Before we can start to use AutoFixture, we first need some example code to work with. So lets imagine that we have a small system that deals with Blogging. In this system there is a blog that authors can contribute to by publishing blog posts that they are associated to (one author per blog post).

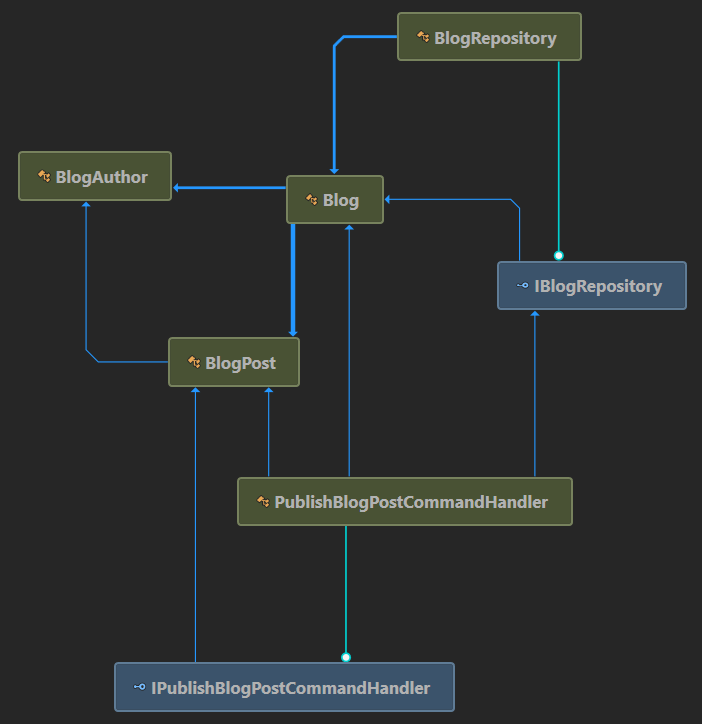

If you open the !(repo for this article)[] you’ll see that I’ve created a simple project to demonstrate this example. In the main project you can see two orchestration & infrastructure classes (along with interfaces), they are PublishBlogPostCommandHandler and BlogRepository.

You can also see a Domain folder, which has an class hierarchy defined to represent the system I described above.

There is a Blog class, which have multiple BlogPosts which in turn have a BlogAuthor.

Our Blog class also defines some methods to allow us to find out some high level info about our blogs such as the latest post title, and to retrieve a list of all the authors that have contributed.

This structure is represented in the following class diagram.

Our example system won’t do much, but what it will do is enforce some rules around the construction of objects to make sure that the users of our domain model (other devs and our future selves) you cannot create instances of classes in an invalid state.

This is very important, I won’t go into this in much detail now, but in my opinion designing your classes so that they cannot be instantiated in an invalid state is one of the corner-stones of good object oriented programming.

If you aren’t enforcing valid state in your code then my advice is that you start doing so as soon as possible, the benefits you will reap can’t be over-stated.

Writing Tests (TDD Style) Without AutoFixture

Before I can show you how to apply AutoFixture first I’ll need to create some unit tests without it.

I like to unit test my domain layers before I worry about implementing orchestration or infrastructure classes so I’m going to focus my efforts there, and for this example I’ll start by testing the BlogPost class.

As I am comfortable using TDD I prefer to drive my code from unit tests, and I have a tendency to make my first test one that just proves I can construct an object (and maybe that it implements a certain interface).

So my first test (followed by an implementation because this is TDD remember) might look like this..

[Fact]

public void Can_Construct_BlogPost()

{

var sut = new BlogPost();

sut.Should().NotBeNull();

}

As you can see there’s not much to the first test that I usually create. One thing I also like to do is keep my asserts in each test down to a reasonable level. I prefer more focussed tests, rather than fewer tests that have many assertions. So working in a TDD style the test we just wrote will ideally stay unchanged, and we will add new tests as we develop our domain model.

Do you remember that I mentioned my classes would enforce rules to make sure that instances cannot be created in invalid states ?

Well in this application creating a blog post without a title, author and postDateTime is not allowed, so I’m going to update the constructor so that it checks each of these arguments are valid. So I’ll start by writing a new unit tests that looks like this..

[Fact]

public void Constructor_Initializes_BlogPost()

{

const string expectedBlogPostTitle = "my test blog post";

var expectedBlogPostDateTime = DateTime.Now;

var expectedBlogAuthor = new BlogAuthor();

var sut = new BlogPost(expectedBlogPostTitle, expectedBlogAuthor, expectedBlogPostDateTime);

sut.Id.Should().NotBeEmpty();

sut.Title.Should().Be(expectedBlogPostTitle);

sut.PostDateTime.Should().Be(expectedBlogPostDateTime);

}

..And then I’ll update the constructor to implement the validation.

But now our original test won’t compile anymore so we need to go back and update it. Now it passes in the arguments the constructor needs..

[Fact]

public void Can_Construct_BlogPost()

{

var sut = new BlogPost("my test blog post", new BlogAuthor(), DateTime.Now);

sut.Should().NotBeNull();

}

At this point I can run the tests and they are all passing.

Adding More Functionality

All looking good so far!

Now I’m going to go and write some unit tests to make sure my BlogAuthor class can also be constructed and enforces its own set of invariant rules, then implement BlogAuthor class. You don’t need to see me doing this so lets have a time lapse…

OK, I’ve updated the BlogAuthor class so that you can’t create an author without a name and there’s a unit test for that.

There was a bit of a problem though. When I updated the BlogAuthor I also broke the BlogPost tests because they create a BlogAuthor to pass into the constructor of the BlogPost, so I had to specify an author name in them too.

They now look like this..

[Fact]

public void Can_Construct_BlogPost()

{

var sut = new BlogPost("my test blog post", new BlogAuthor("john.doe"), DateTime.Now);

sut.Should().NotBeNull();

}

[Fact]

public void Constructor_Initializes_BlogPost()

{

const string expectedBlogPostTitle = "my test blog post";

var expectedBlogPostDateTime = DateTime.Now;

var expectedBlogAuthor = new BlogAuthor("john.doe");

var sut = new BlogPost(expectedBlogPostTitle, expectedBlogAuthor, expectedBlogPostDateTime);

sut.Id.Should().NotBeEmpty();

sut.Title.Should().Be(expectedBlogPostTitle);

sut.PostDateTime.Should().Be(expectedBlogPostDateTime);

}

But There Are Problems…

On the face of it our tests are helping us verify we haven’t introduced faults into our system as we develop it, and so far the tests are fairly simple to understand. But we have enough here already to highlight some issues…

-

When we introduced our second unit test which added constructor arguments to our

BlogPostclass we broke our firstCan_Construct_BlogPosttest. It didn’t just fail, it wouldn’t even compile. -

When we introduced constructor arguments into our

BlogAuthorclass we broke both of ourBlogPosttests because they had to supply an author name. They also won’t even compile.

To sum it up…

What we have here is a form of brittle unit tests - our implementation changes are forcing us to go back to unit tests and rewrite parts of them in someway (as opposed to the tests failing because the outcome has changed). As the number of tests grows, so does the amount of work we need to do to maintain the test projects when we work on our application implementation.

We can also make some observations about the two BlogPost tests we wrote

-

The BlogPost Can_Construct test does not need to care about the test data used

The BlogPost Can_Construct test does not even assert what the properties of the constructed blog post are, it only uses the test data to constructs an instance and prove it was constructed. Nothing more. \ -

The Constructor_Initializes_BlogPost also does not care what the values of the constructor arguments are.

Hang on a minute, this is a little bit more interesting. We can see that the test asserts that the test data passed into the constructor becomes the values of the properties. So how can the test not be interested in the values ?

Well I can say that because the test is to make sure that the properties are set to the values injected into the constructor. What the values are is irrelevant; what counts is that valid arguments become property values.

Oops

At this point I want to mention that when implementing the code I noticed a mistake in our example project. The BlogPost class was missing a key piece of data - an actual body post body!

So I went back and added it, breaking all those existing unit tests again and further demonstrating the problem I’m describing here.

One Last Demonstration Of The Problem

Anyone who has written or maintained unit tests in a real world system will know that they can be a lot larger and more complex that what we have in this application, particularly if they are poorly written.

But if you’re not quite convinced yet I want to give it one more try. Let me fast forward time and show you what a unit test will look like for our command handler based on the domain model as it stands now.

The command handler will take a blog post, publish it to a blog and save the blog back to our database via a repository, that’s not complex functionality.

Here’s what the test will look like..

[Fact]

public void Handle_Calls_Repository_Update_With_An_Updated_Blog()

{

var expectedAuthor = new BlogAuthor("test blog author");

var expectedBlogPost = new BlogPost("test title", "test body", expectedAuthor, DateTime.Now);

var expectedBlog = new Blog("My test blog");

var mockRepository = new Mock<IBlogRepository>();

mockRepository.Setup(x => x.GetBlog(expectedBlog.Id)).Returns(expectedBlog);

var sut = new PublishBlogPostCommandHandler(mockRepository.Object);

sut.PublishPost(expectedBlog.Id, expectedBlogPost);

mockRepository.Verify(x => x.Update(It.Is<Blog>(b => b.Posts[0] == expectedBlogPost)), Times.Once());

}

Our tests become more complicated, we now have 5 lines of setup code before we can instantiate the class we are testing and call PublishPost on it, and then verify that the repository was Update method was called.

Isn’t This What Mocking Solves?

If you have some experience writing unit tests you are probably thinking that we could overcome some of the problems I’ve shown above by introducing interfaces for the Blog, BlogPost and BlogAuthor classes, and that’s certainly an option you might choose.

But when create domain layers I try to limit defining them for aggregate root classes, I don’t define them for any other entities or values if I can avoid it.

After years of writing software by applying test driven design, I believe that one should be careful in choosing what to mock and even more careful in considering when to verifying that mocked methods are called. Mocking out interfaces can easily lead to tests that focus on how classes are implemented instead of the outcomes of the class. This prevents us from refactoring code without breaking tests even more than the example I tried to show above.

So to avoid this I try to limit mocking to only orchestration and infrastructure classes, and I only verify method calls when absolutely necessary. Later in this series I will however show you how AutoFixture can automatically mock interfaces fo you.

Part 2 - Adding AutoFixture

In part two of this article I will show how to introduce autofixture to your unit tests to solve some of the issues demonstrated in this article.